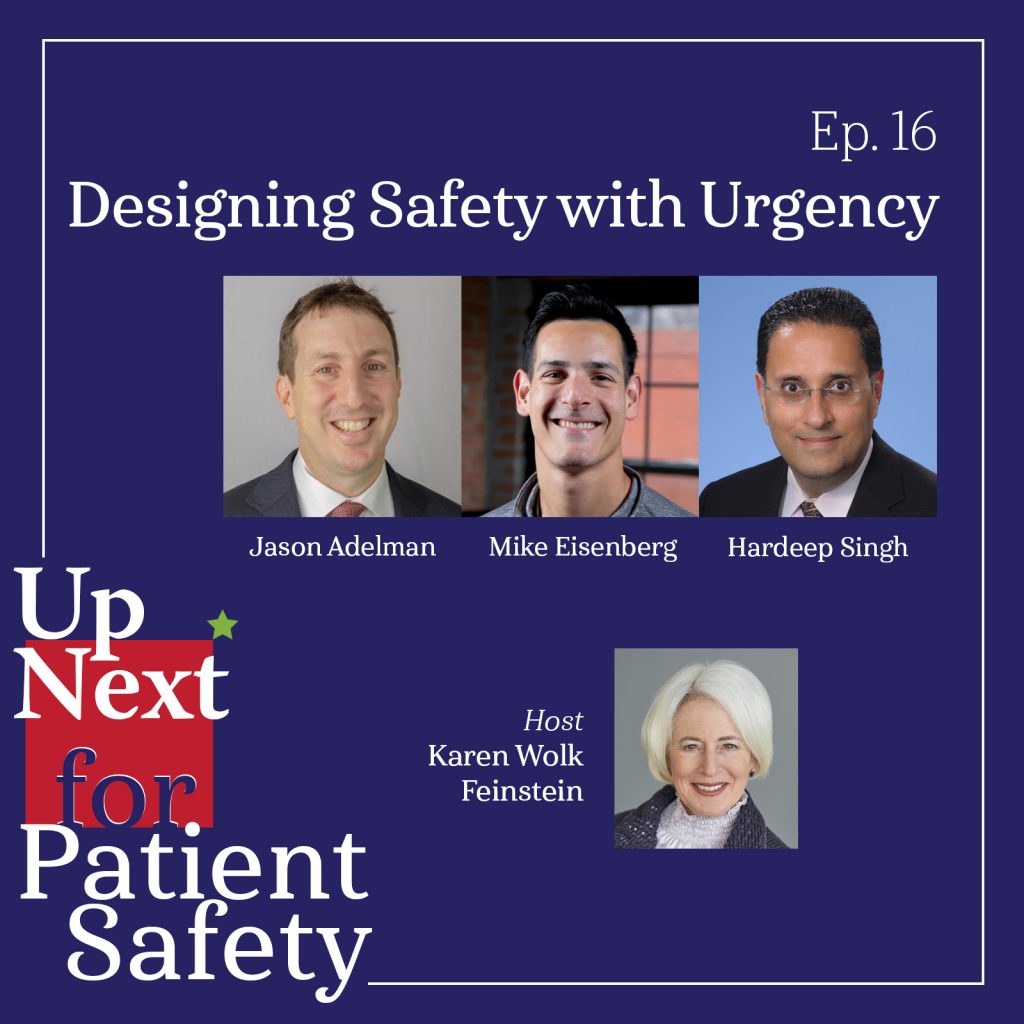

Episode 16: Designing Safety with Urgency

How can we close the implementation gap to translate patient safety research into practice? What role can technology play in this process? Join host Karen Wolk Feinstein and two award-winning researchers, Dr. Hardeep Singh of Baylor College of Medicine and the Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center, and Dr. Jason Adelman of Columbia University Medical Center/New York-Presbyterian Hospital, along with filmmaker Mike Eisenberg of Tall Tale Productions, for a glimpse into the pioneering patient safety research happening today and the promise of tech-enabled solutions to equip clinicians in designing safer systems.

Listen to this episode on: Apple Podcasts | Spotify

Featured Speakers

- Jason Adelman, MD, MS, Chief Patient Safety Officer & Associate Chief Quality Officer, Columbia University Medical Center/New York-Presbyterian Hospital

- Mike Eisenberg, Partner/Creative Director, Tall Tale Productions

- Karen Wolk Feinstein, PhD, President & CEO, Jewish Healthcare Foundation & Pittsburgh Regional Health Initiative

- Hardeep Singh, MD, MPH, Professor of Medicine and Chief of the Health Policy, Quality & Informatics Program, Center for Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness and Safety at the Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center and Baylor College of Medicine

Referenced Resources (in order of appearance):

- Up Next for Patient Safety – Bonus Episode 01: Twin Crises

- Beyond ‘John of AHRQ’ — John Eisenberg at Penn Medicine, Wharton and LDI: A Profile of One of the True Greats of Health Services Research (Penn LDI, 2017)

- John M. Eisenberg Patient Safety and Quality Awards (National Quality Forum)

- The Joint Commission and National Quality Forum announce 20th annual Eisenberg Award recipients (Joint Commission, 2021)

- Patient Safety Technology Challenge

- Congratulations 2022 Eisenberg Awardees (Joint Commission, 2022)

- The John M. Eisenberg Excellence in Mentorship Award (AHRQ)

- 26 Patient Safety Experts to Know | 2022 (Becker’s Hospital Review, 2022)

- Understanding and Preventing Wrong-Patient Electronic Orders: A Randomized Controlled Trial (Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 2013)

- To Err Is Human (Documentary)(Tall Tale Productions, 2019)

- To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System (Institute of Medicine, 1998)

- Health Policy, Quality & Informatics Program Investigators

- Improving Diagnosis in Health Care (Institute of Medicine, 2015)

- From Plans to Actions: Closing the Implementation Gap for Patient Safety (The Lancet, 2023)

- Center for Patient Safety Research Impact (Columbia University Department of Medicine)

- Effect of Restriction of the Number of Concurrently Open Records in an Electronic Health Record on Wrong-Patient Order Errors (JAMA Network, 2019)

- Use of Temporary Names for Newborns and Associated Risks (Pediatrics, 2015)

- AHRQ PSNet Annual Perspective: Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Patient Safety (ARHQ: PSNet, 2021)

- Health Care Safety during the Pandemic and Beyond — Building a System That Ensures Resilience (New England Journal of Medicine, 2022)

- Implications of the COVID-19 pandemic for patient safety: a rapid review (WHO, 2022)

- Joint Commission Center for Transforming Healthcare Survey: Nearly 2 Million Health Care Professionals Don’t Feel They Have Tools, Training to Safely Care for Patients (Business Wire, 2019)

- Measurement of Patient Safety (AHRQ: PSNet, 2019)

- Fighting a Common Enemy: A Catalyst to Close Intractable Safety Gap (BMJ Quality & Safety, 2021)

- Don’t Freak Over Boeing’s Self-Flying Plane—Robots Already Run the Skies (WIRED, 2017)

- Survey: Nearly All U.S. Hospitals Use EHRs, CPOE Systems (Healthcare Innovation, 2017)

- Atul Gawande’s ‘Checklist’ For Surgery Success (NPR, 2010)

- Peter Pronovost: champion of checklists in critical care (Lancet, 2009)

- Reconsidering the application of systems thinking in healthcare: the RaDonda Vaught case (British Journal of Anaesthesia, 2022)

- Human Factors Engineering (AHRQ: PSNet, 2019)

- Overconfidence as a Cause of Diagnostic Error in Medicine (American Journal of Medicine, 2008)

- Alarm Fatigue and Patient Safety (Anesthesia Patient Safety Foundation)

- Diagnostic Error in Internal Medicine (Archives of Internal Medicine, 2005)

- Winners of the 2023 Breakthrough Prizes in Life Sciences, Mathematics and Fundamental Physics Announced (Breakthrough Prize, 2022)

- Introducing Artificial Intelligence Training in Medical Education (JMIR Medical Education, 2019)

- AI Feared as Job Snatcher by Nearly Half of Healthcare Workers (HealthLeaders, 2023)

- U.S. Health Care Leaders Embark on International Study Tour for Knowledge Exchange in Health Care and Policy (Academy Health, 2023)

- Violence Against Nurses Tackled Using Virtual Hospital Visitor Angry Stan (ABC Australia, 2019)

- Virtual Reality and the Transformation of Medical Education (Future Healthcare Journal, 2019)

- The Potential for Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare (Future Healthcare Journal, 2019)

- Significance of Machine Learning in Healthcare: Features, Pillars and Applications (International Journal of Intelligent Networks, 2022)

- Use of Deep Learning to Develop Continuous-Risk Models for Adverse Event Prediction From Electronic Health Records (Nature Protocols, 2021)

- Reimagining Better Health Study (GE HealthCare, 2023)

Episode Transcript

[00:00:00] Jason Adelman: And I can tell you the most brilliant brain surgeons in the world still make errors. Humans make errors.

[00:00:09] Hardeep Singh: Sort of come together and say, okay, we do have a common enemy. How do we make resource investments to fight that common enemy?

[00:00:16] Mike Eisenberg: Today, technology is changing the way patient safety efforts operate right now, and is only gonna help a lot of the problems that exist in health care get solved.

[00:00:30] Karen Feinstein: Welcome to the second season of Up Next for Patient Safety. We’re thrilled to continue to share conversations with the most interesting people, doing the most important work, part of our common goal of making health care safer.

I’m your host, Karen Feinstein, president and CEO of the Jewish Healthcare Foundation and the Pittsburgh Regional Health Initiative, which is a multi-stakeholder quality collaborative here in my hometown. We’ve been working to reduce medical error for over 25 years, and I will say at the start, we never believed the progress would be so slow.

However, I do know that revolutions come from hope and not despair. We hope these conversations will inspire all of us with hope as we hear from safety leaders of distinction in last season’s bonus episode on the Twin Safety Crises and related crises of a shrinking healthcare workforce and an increase in adverse events, we touched upon the pioneering safety work of the late Dr. John Eisenberg during his time leading the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality or AHRQ. John was a giant without whom I wouldn’t be here today. On today’s episode, we talk about how John’s legacy has inspired the work of today’s patient safety leaders with two recent Eisenberg patient safety and quality award winners, as well as the filmmaking work of John’s son, Mike.

Today we’ll hear from Dr. Hardeep Singh, who is a professor of Medicine and chief of health policy, quality, and informatics at the Center for Innovations, Quality, Effectiveness and Safety, known as IQuESt, at Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center and Baylor College of Medicine. He received the Individual Achievement Award at the 20th John M Eisenberg Patient Safety and Quality Awards in 2021 for his achievements in the creation of diagnostic and IT safety tools, foundational research on defining and measuring diagnostic error, and the development of the National Veterans Affairs tool for safely communicating test results to patients and providers. His work has influenced many organizations, including the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid, the Department of Veterans Affairs, the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology, National Quality Forum, the Joint Commission, the AMA, and many others.

We also have with us Dr. Jason Adelman, executive director of the Center for Patient Safety Research and the director of the Patient Safety Research Fellowship at Columbia University’s Irving Medical Center in New York Presbyterian Hospital. He is also an associate professor of medicine and vice chair for quality and patient safety in the Department of Medicine at the Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons. He is also a member of our Pittsburgh Regional Health Initiative Patient Safety Technology Challenge Advisory Board. In 2022, he received the Individual Achievement Award at the Eisenberg Patient Safety and Quality Awards as well, at the same time as the John M. Eisenberg Excellence in Mentorship Award from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality for establishing the first federally funded patient safety research fellowship for hospitalists. And to add to this wonderful year of 2022, he received Becker’s Hospital Review recognition as one of the 26 patient safety experts to know. Jason is a leader and innovator in developing novel methods to measure and prevent errors in health IT systems. Among his key accomplishments is the development of the wrong patient, retract and reorder, or RAR, measure that detects wrong patient orders in electronic health record data. As executive director and founder of the Center for Patient Safety Research, Jason has led several National Institutes of Health and AHRQ funded projects to test safety interventions. Welcome Jason.

And our third participant today is Mike Eisenberg, the son of John Eisenberg, but a patient safety leader in his own right. With more than three years of production on the acclaimed documentary To Err Is Human and countless hours of interviews with experts in medical error, Mike has gained incredible insight into safety problems and progress. In addition to being a celebrated filmmaker, Mike also had a career in a most unusual field as a professional athlete. He was drafted in the 2006 Major League Baseball draft by the Cleveland Guardians. Prior to joining baseball, he helped lead Marietta College to a Division III National Championship while earning multiple accolades, including first team All-American. So, welcome Mike as well.

So, Mike, let me begin with you. I came to know your dad during his term as AHRQ director from 1997 to 2002. He dedicated his professional career to the use of evidence-based research in healthcare decision-making and laid the foundation for decades of patient safety work. Tell us a little bit about how you came to create your film To Err Is Human and what your father’s work meant to you in your filmmaking.

[00:06:23] Mike Eisenberg: Well, thanks, Karen, for the introduction and the question. The documentary that we produced just prior to COVID about patient safety was really in earnest, supposed to be a documentary about AHRQ and came about because my father’s role in the agency was so significant in my own understanding of his career.

Now my family and I had always sort of kept an eye on whether AHRQ was going to get the funding it always requested each year, and we were part of newsletters, and a newsletter had come out saying that, you know, there’s another potential that it could be defunded. At the time, politics was getting hotter and hotter and agencies like AHRQ were becoming more politicized.

And it raised a red flag for me. We can’t let this happen without trying to help the general public understand the role AHRQ has in health care and any success that it has. So, we started interviewing people who we knew were close to my father, like Carolyn Clancy and Helen Burstin and Lisa Simpson and others. And immediately we realized there’s a much bigger story about patient safety that really has not been told yet. We always hear the negative headlines. We always hear these terrible things that happen in health care and sometimes even the really bad people who are doing things because they shouldn’t even be in health care in the first place, but nobody really talks about the work being done in patient safety that had been done for up to 20 years at that point, if not more, led in some ways by the work that my father had done. So, this was an opportunity for me to revisit my father’s legacy and get a better sense of who he was and what he did, because when he passed, I was 17 years old, I didn’t really know much about health care or, let alone research-based work in health care. And now as a filmmaker, I had a chance to interview people and learn more, and it became evident that there’s a lot of really great work being done in patient safety, and it deserved to be highlighted. So, we took it upon ourselves to take the bigger journey. That took three years of finding those stories all across the country, and even in Canada, of people doing really incredible work on patient safety from the ground up.

And, I think in doing that, we found a really great opportunity to share this story with the healthcare community. We screened it over 260 times across the country. We reached eight different countries, and it continues to be screened. We have screenings in Taiwan in the next couple weeks. So, it’s really amazing to see how powerful the story of patient safety can be when you tell the story in a compelling and positive way.

And show the work being done. So, we are going to continue doing that as, as much and often as possible and stay in this field, and I’m grateful for the opportunity to share any insights I’ve learned along the way with you today, but also hear from Jason and Hardeep on what they’ve seen.

[00:09:25] Karen Feinstein: Thanks Mike. And we’ll be talking later. You will get an opportunity also to take those insights into a second documentary, but we’ll be talking about that. Also, I do wanna note that a previous podcast in our series we interviewed Lisa, Helen, and Carolyn, and talked about their work at AHRQ and their work with your father.

So Hardeep and Jason, you know each other well, having worked together on diagnostic errors in pediatric care. So let me turn to you, Hardeep, first, much of your work has focused on translating research into action for improving patient safety. Tell me, how has your research changed the landscape of patient safety and where do you see your own patient safety research heading?

[00:10:12] Hardeep Singh: Thanks for having us on here. So, as you know, I started my career off as a diagnostic safety researcher back when there was not a lot of focus on diagnostic error. In fact, when I was a clinician and wanted to become a researcher and try to get funding, I failed multiple times just because there was not enough research funding in this area, and I almost gave up.

But we’ve come a long way since then because we’ve defined the problem of diagnostic error much better. It was something that was not very well covered in the initial To Err Is Human IOM report, but since then we’ve created sort of this body of research in a portfolio that is almost like a burning platform that defines the problem of diagnostic error, but also offers measurement and solutions.

So we’ve tried to create some tools and resources for people to, you know, look at the problems within the healthcare systems. And I’ve really been sort of gratified to build a multidisciplinary team to help me do that. Through these tools and through this body of evidence, we’ve been able to also influence policy makers. We’ve been also been influencing funding bodies. As to what they should be funding in this work. So essentially, you know, we’ve, we’ve tried to sort of push the boundaries on making diagnostic error a priority over the last, you know, decade or so. And as you know, now there’s been an Institute of Medicine report on the topic of diagnostic errors, which came out in 2015.

We’re very fortunate that it cited a lot of our work, including the fact that this is a very common problem. Almost all of us will have a diagnostic error at least once in our lifetime. So, we’ve got a long way to go in terms of research in this area, and we’re making good strides. So, I think we’ve come a long way and through good investments.

I’m very thankful for research funding from the VA and from AHRQ and from the Moore Foundation that have really invested in the body of work on diagnostic errors.

[00:12:18] Karen Feinstein: Well, I would say when any of us talk about diagnostic error, your name comes up. Where is your future research heading, do you think?

[00:12:29] Hardeep Singh: I think most of this is not gonna be translational. I think we’ve created enough evidence. You know, as a researcher, we like to sort of publish papers, right? And hopefully someday somebody reads that paper, and you know, a lot of this published research just sits on the shelf, and nothing happens. And so, over the last sort of five to seven years, my focus is more on translation. How can I work with health systems to translate the body of research that I’ve created, or we’ve created, my team has created, and so have others, in changing the way we practice medicine? I mean, what’s the point of doing research? Unless you can impact patient care, unless you can improve the lives of patients, and also of clinicians and health systems, right? So, we have to sort of improve the health system. We have to improve sort of the way we practice medicine. And unless we can do that through research, what’s the point of doing all this research? What’s the point of all this data and evidence? Unless we can translate that. So, we know that patient safety research has a huge implementation gap. So, for the next few years, what I hope to do is to work with, you know, both sort of health systems and policy makers to translate all that evidence into practice and improve the lives of patients

[00:13:46] Karen Feinstein: Well, we’re cheering you on. We need that translation, sooner rather than later. Jason, your own research focuses on developing systems-based solutions to prevent medical errors. Can you share some of the interventions that you and your team have developed and maybe tell us also what might be on your drawing board?

[00:14:07] Jason Adelman: Thank you, Karen, and thank you for having me. A lot of my research is based on the use of automated measures that capture patient safety events. That’s, I think my, been my biggest innovation and contribution and these automated measures, the first one I developed, was to identify when orders are placed on the wrong patient, and once, and the way it works is quite simple. It looks for when a doctor places several orders on a patient, cancels them, and then orders them on another patient. The program I used to work with used to call it the oops query, like, oops, I’m on the wrong patient. But that automated measure, at any average size institution, there can be anywhere from 5,000 to 10,000 orders placed on the wrong patient. When you have that many, they’re all near misses that we identify, like thankfully they’re caught before they reach the patient. But it’s allowed a lot of novel things to happen. So first, it’s a very accurate reflection of errors. It doesn’t rely on voluntary reporting that has biases or chart review that has different biases. If somebody places an order on the wrong patient, they’re gonna fix it, and then we’re gonna know, and there are so many of them that it’s allowed me to do studies that were not possible before. So, I do a lot of large randomized trials within the EHR using automated measures. So, I answered a research question or, or investigated a research question, do multiple records open at the same time lead to orders placed on the wrong patient? To answer your question more directly, what are my innovations, or what are the like very simple interventions that I evaluated, but it was only possible because this automated measure was fixing how babies are named when they’re born.

Before my research, most babies were given some temporary name, like baby boy or baby girl because parents don’t have the names ready to go, and so the hospital needed something. The easiest thing was for labor delivery to call admitting and say, Mrs. Adelman had a baby, and it’s a boy. They’d copy the record, just name the baby Baby Boy Adelman. But those that were admitted to the neonatal ICU, it would be, you would have Baby Boy Jones, Baby Boy Johnson, Baby Boy Jackson. And so, we demonstrated with an automated measure of wrong patient errors that this is very error prone, somewhat obvious. We some ways proved the obvious, and then we used a simple intervention of using the mother’s first name. Judy’s boy. Karen’s girl, Cynthia’s boy. And that led to enough distinction that it decreased wrong patient errors by 40%, and the Joint Commission made it a requirement. But it, again, it was only possible because of the automated measures. So, my intervention was simply changing the name, but none of that would’ve been known or possible without these automated measures. And now I’m making more of them for other types of errors, wrong dose, wrong route, wrong frequency, and so forth.

[00:16:59] Karen Feinstein: So, a simple intervention, but a critical one. Thank you. And I guess that’s why Becker’s Hospital reviews it. We should keep our eye on you over the next year. So, we will. So, both Hardeep and Jason, we’re reading credible reports of how progress and patient safety has stalled, not only stalled, but regressed, since the start of the pandemic. What are the key drivers of this unfortunate trend, and can you tell us how we might reverse it? How we might get more energy, more urgency put into this issue of medical error? Hardeep, do you wanna go first?

[00:17:43] Hardeep Singh: So, Karen, I was privileged to lead a report from WHO on the implications of the COVID pandemic on patient safety. And one of the things we found was, Yes, there has been a slowdown on multiple fronts. There’s been many reasons, right? So even before the pandemic, we used to have issues with investments. And what I mean is not financial investments, just resource investments and considerations to improve patient safety.

And of course, the pandemic was a huge distraction to that. You know, people used to ask me, Hey, did diagnostic errors go up or down during the pandemic, and I think, well, I think they went up. But the measurement of patient safety has been such a challenge to begin with. We have no idea. Right? I’m fairly certain that where we were doing good measurements such as healthcare-associated infections and things like pressure ulcers, all of that data is coming out now and said, yep, we got worse. Why? Because we were doing measurements in the area. But such a large proportion of patient safety problems are not measured. I mean, we rely on reporting, but guess what? People stop reporting during the pandemic. Well, people also got deployed, so the quality and safety people at multiple hospitals and health systems were not really working on quality and safety. They got deployed to do other things. At the same time, the clinicians were distracted, the nurses were overwhelmed, and so there was not a lot of, you know, efforts that could be sort of, focused on patient safety per se, because we were in survival mode and we were barely, you know, getting through. So, it’s understandable that there was lack of, there was sort of, you know, the progress was slowed down. Now the question is, what do we do about this? What lessons can we learn?

We did do very well in some of the things in patient safety. In fact, we wrote a paper about this, that several positive things happened during the pandemic too that we can sort of learn from. We were much better at communication. We were fighting a common enemy, so we used to talk to each other in my Texas Medical Center, all the competing hospitals got together for the first time and fought the pandemic, you know, and they shared data. They coordinated care. I mean, they used to meet every day. And these are all competing hospitals because they were fighting a common enemy. And I think the same thing needs to happen for patient safety. Because we need to sort of figure out how we can sort of, as a health system work together and fight this common enemy. And so I think even though there has been a slowdown, there has been some tremendous lessons coming out of the pandemic. Much of it we summarized in the WHO report as well, so I’d like, you know, people to look at that. But it’s time that we sort of come together and say, okay, we do have a common enemy. How do we make resource investments to fight that common enemy?

[00:20:49] Karen Feinstein: I’m so in agreement. I’m amazed often when I talk to leadership and how systems about patient safety going up during the pandemic. And what they wanna talk to me about is how we measure it. We need to measure it better. And you know, my sense is you need to redesign your system for safety with urgency. And I know during the pandemic, at least two cities I looked at, Dayton, Ohio, Salt Lake City hospitals did come together. They crossed borders, corporate borders and worked together with that kind of urgency. And now I’d like them to focus on how you design systems for safety and not talk to me about how we get better measures. Anyway, that’s personal, but thank you. Jason, how are we gonna get urgent about safety?

[00:21:37] Jason Adelman: As far as getting urgent, I think, you, Karen, yourself and Hardeep are both doing such a great job being a voice of patient safety and helping establish it as a crisis that needs attention and serious attention from leaders. My just personal view of what actually will help us be safer is really leaning even further into technology. I have the privilege of working at an Ivy League medical center where everybody around me is just absolutely brilliant and I balance my operations job and my research, and my operations job, I chair every root cause analysis at Columbia, and I can tell you the most brilliant brain surgeons in the world still make errors. Humans make errors. They make errors because, they were up too late or they’re distracted because their partner might want a divorce or their child is sick, or just because we make errors, and I think that to really have a high reliable system like the airline industry right now, the pilot and co-pilot can fall asleep and the plane will fly itself. In health care, I’m making these numbers up, but it’s something like 97, 98% humans and 2% technology, where making a smartphone is 95% technology and 5% humans. But it feels like we’re at a tipping point of, like, being able to better introduce technology into health care. It’s very new, but I think personally, that like ChatGPT, not the application itself, but like just, for me personally, I did not realize the power of AI, and I think it raised awareness for many, many people and it also started like an arms war of AI. And so the ability, like humans will make errors, but technology, I really can think, help, just like it did in the airline industry and other industries, help us become more reliable.

Now, there’s a lot of work to do. It has to be done very carefully and safely. And I’ve heard Hardeep speak on this topic like it’s not like next year all problems will be solved, but thankfully over the last few decades through meaningful use, so many hospitals have replaced handwritten orders with electronic orders and sort of, like, optimized the EHR, so the best that we could, so at least that we have electronic data. We have humans interfacing with computers. Now, if we can do a good job in giving that guidance, if the big EHR vendors like take advantage of some of this AI technology and us researchers do a careful job evaluating both the performance of the AI and how it, as Hardeep said before, how we safely translate it to actual patient care. I’m hoping that that will give us a jump forward in high reliability ’cause humans will make errors. We can use Atul Gawande and Peter Pronovost checklists, but we’re still humans and so we’ll still, you know, make errors. That’s my personal feeling.

[00:24:30] Karen Feinstein: Well, it’s interesting, I, along with so many others, have been involved in groups that spent probably too much time analyzing the RaDonda Vaught episode at Vanderbilt University. And, you know, the idea that that led to individual blame instead of system redesign and not only system redesign, our safety technology may need to be redesigned. We could do so much more, I think, if we had safety technology that performed at its highest. So, I resonate so much with what you’re saying.

And also, Jason, as you know, it’s been interesting to watch our Patient Safety Technology Challenge, where we want to inspire young innovators. Really young, even some high school students, to address patient safety through technology, to come up with technology-based solutions. When we started that, we said, this is a wild experiment. We’re not sure universities are gonna jump in, that datathons and business school competitions and hackathons, the people are gonna be interested in patient safety tech. We never expected the uptake that we got. This has really been rather extraordinary at some of our leading institutions after leading institution. Young people are really getting into this. We’re, we’re recruiting some young pioneers. So just as a last thought, both Hardeep and Jason, if we were thinking outside the box on things that maybe are radically new, do you have anything else either of you wanna add that we need to do and encourage and incentivize to get this urgency that really, the current rate of medical error demands?

[00:26:25] Hardeep Singh: Maybe some of the solutions need to come within the box. It’s just we haven’t been looking at it. I often think that, you know, I don’t think we invest as a health system enough in safety, and as I said before, when I say invest, I mean, you know, dedicate time, resources, energy, all of that, including clinicians, including, you know, health system leaders. I feel that we don’t work in multidisciplinary groups. This is not a problem clinicians will solve or the health system leaders will solve. I think we’re gonna have to work together with multiple sorts of multidisciplinary groups. So, in our work, we often will include human factors, informatics, social science, behavioral science, implementation, science, health services, research, clinicians. All of those people in our work, because you need these multiple perspectives. Everybody thinks there should be some like magic bullet that’s gonna solve some safety problem. It’s never gonna be like that. Even with the best of technologies, we need design principles. We need sort of these human factors principles that guide us through this implementation of technology is using a sociotechnical lens.

An AI platform is not gonna solve all the patient safety problems that we have in the world. I’ll just give you one example. We found that, you know, for, you know, diagnostic errors, clinicians are often overconfident and won’t seek help when they most need it. So, you could have the best AI platform in the world, but if the physicians are not going to use it, what’s the point? And so I think we need to sort of think about how we can work through some of these design issues. I think Jason alluded to this as well, and some of those come from within the box, and I think we have an implementation gap that we need to close. We’ve got the tools, the processes, the technologies, the, and the people, right? And we need to now sort of create the right combination through serious dedicated resources to invest in patient safety.

[00:28:29] Jason Adelman: So, I can add to that. I mean, I already sort of stated I am personally a big believer in technology and I do think there is opportunity in AI, but I also take Hardeep’s point that there are all of these incredible, incredibly brilliant people that are trying to make accurate predictive models that will tell us when a patient has a disease that the doctor might miss, they’ll predict an event. But then, taking that information and then translating to actually helping the patient is a whole other world that is not really well, that we haven’t solved. So we can have all the great predictive models in the world, but if we can’t figure out, you know, if we give them an alert, we know we have a major alert fatigue problem, so that might not work. Hardeep was talking about there are all these cognitive biases in health care. So, doctors have their premature closure as one of the cognitive biases, and computers might be able to help them overcome these cognitive biases. They’ve locked in on a diagnosis too early, and so what is the right way that once the computer, through a great predictive model, knows what the diagnosis is, and the computer is right, and the doctor thinks it’s something else. How do we have them interact? And I don’t know that anybody solved that problem yet. And so, like, I’m personally in fact more interested in that. I’m sort of allowing all the brilliant minds to work on the predictive models and I’m interested in evaluating interventions that will help improve patient care, creating those interventions, and then evaluating them.

So there’s a lot of work still to do, and when I say I believe technology will really help, I still think it’s gonna be decades. I’m excited, like what I’m seeing, I feel like AI is just much more powerful than I ever realized. And so I’m, I’m hopeful, but still a ton of, ton of work to do. And I wanna just add, Karen, your Challenge I think is great. It’s just Inspiring people that otherwise are sort of outside, potentially, health care with a billion ideas to come in and solve a problem. The world was trying to have computers figure out how proteins fold for many, many years, and then somebody created a million-dollar challenge and within a year they solved the problem, outside thinkers came in. So I just love what you’re doing with these technology challenges, and I’m hopeful that will play its role and, and it’s a good model for change.

[00:30:55] Karen Feinstein: Of course you bring up a topic we won’t have time to get into, but we should in a future conversation, the way that physicians and other clinical professionals relate to AI and to technology- enabled care reminds me, is it time to revisit medical education? Are we really using the time of our students in medicine and nursing and pharmacy? Is it in tune with a new era? I mean, things are changing so fast and yet my observation is that education seems stuck. I don’t see it dealing with these issues that you’re raising that that health care in the future is gonna be tech enabled. It is gonna be a partnership between human, machine, and big data and important analytics. I really do wish we were revisiting what do we do with the time that our clinical scholars put in to preparing for work in a new world? But that’s obviously a topic that you’ve raised for another conversation. I know, Mike, you wanted to add something to this.

[00:32:12] Mike Eisenberg: Yeah, well, and even just transitioning off of what you just said, you know, I’m seeing quite a lot of progress in the education side of how we’re training the next generation of doctors and nurses and surgeons. There are tools that exist today that are being used in a lot of educational settings and, and they are the tools of, that seem like the tools of the future, but they’re used in other industries today, like virtual reality, or, you know, high tech visual learning tools. The point I want to make anyway is the problem in health care is it has a PR problem, right? When it comes to patient safety and when it comes to innovation. It’s a problem of perspective. People don’t look at health care, and some do, but in general, people don’t really look at health care as a place to take their bright ideas. And I’m talking about, you know, some of the younger generations, the people who are coming up who can put their ideas and their great minds to use in other industries that have a great history of accepting innovation and doing it quickly. And health care is an extremely intimidating field to do anything in and let alone be a clinician.

And the healthcare systems today need to start engaging the next generations on how to solve the problems that exist because they want to find new ways to solve the problems. I’ve been talking to these people, whether they’re coming from the innovation challenges that JHF is funding, or they’re in health care. There’s people in health care right now that are undergrad, but also ones that are graduate students about to enter the clinical workforce, who have lived their entire life in this tech age, or they may know what it’s like. They understand how coding works, they understand how the newest technology works and they want it to be part of their healthcare experience in terms of how they deliver health care.

And they’re entering an industry that is a little behind on that. Yes, the tools are coming out and when you engage the next generation, the people who are gonna be using the tools that are developed today, in the future, you can probably get there a lot faster and, and that’s what’s gonna be hard for health care, I think to do, because there’s a way things have been done and those people sort of run the show, and I think when they start to listen to the 20 and 30, even 40 year olds who are lived with this technology and are comfortable using it and want to see it brought in, you start to see it as more of an opportunity and less scary.

And I think when you see these statistics on AI and health care and the fear of it taking over and replacing jobs, I don’t know who they’re asking these questions to. I don’t know if it accurately represents the people who are entering health care, the next generation who want to be using AI, who want to be using technology to enhance their skillsets and their ability to perform good quality care. I think we all agree that everybody in health care’s overworked and they’re understaffed. Technology can be used as a tool to supplement the things that they shouldn’t be doing and allow them to get back to the patient centered care that they got into this in the first place to do. And we can use AI to enhance that rather than replace that.

[00:35:42] Karen Feinstein: It’s interesting. One of the most emotional moments I’ve ever had giving a talk at NBME was when I referred to patients as consumers. And it was so funny. It was a very controversial talk. I thought that was the least of it. But there was a doctor who had total meltdown in referring to a patient as a consumer. But I do think of myself as a consumer. So anyway, one thing also that I’m intrigued with, with the Patient Safety Challenge, is how we really pushed it to be interdisciplinary and that kind of interdisciplinary work is something, Hardeep and Jason, we may, we may need some physician comfort with the fact that ideas come from other places.

And I’ll just quickly say, we did a study tour recently. Commonwealth Fund put it together and we were in Australia talking to nurses. And the nurses have gotten very much engaged in technology and informatics, and they were showing us something the nurses had developed. It’s AI facial recognition. So there’s been a lot of violence there as we have here against healthcare workers. And the nurses put together an AI facial recognition that can talk about people in waiting rooms and other places who are starting to get very agitated. And then the nurses developed a virtual reality training program for other healthcare workers on how to defuse anger. And I thought, and then they said to us, well, we’re sure you’re way ahead of this in the U.S. Actually, we’re not.

But I thought that was very intriguing. So, we all see some great potential for technology, and we want to apply the best of it, but also prepare people to work alongside it, to take advantage of it, but to bring their own ingenuity into the process. So, we do think the Patient Safety Technology Challenge is the beginning.

So I’m involved with a lot of informal groups, some more formal than others. Solutions for Patient Safety, CLEAR, Patients for Patient Safety, PACT. I know there’s work going on, Hardeep, at the World Health Organization, AHRQ has a new alliance, and we have our National Patient Safety Board Coalition of over 80 organizations.

We’re turning to Mike to try and pull together some of the ingenuity, the thinking that’s coming out of the patient safety technology. Pull a lot of thoughts together about a brave new world where a multidisciplinary group of professionals come together and use technology to its max while being aware that we don’t wanna introduce other errors. So do you wanna say a couple words, Mike, about the documentary you’re putting together to help us pull together some of these thoughts?

[00:38:39] Mike Eisenberg: Yeah, it’s been a really fascinating journey so far. And we started it in, you know, in earnest in the fall, really just starting the research phase and as documentaries go, it’s dramatically different now, as it probably will be by the end of this year.

But it’s a really compelling part of the story of patient safety. I mean, as we’ve talked about today, technology is changing the way patient safety efforts operate right now and, and is going only, is only gonna help a lot of the problems that exist in health care get solved. It won’t solve everything. Nothing can, but it can really close the gap on what ends up causing harm to patients. Because we as humans do make mistakes, right? And computers allegedly don’t, but we know that they can, if the code is wrong or if it’s developed poorly, because humans make those programs at the same time. And if you take a closer look, the technology that’s being developed for healthcare of the future, every single part of that space is being utilized by somebody right now.

And there’s, there are VR tools being used to solve some of the challenges in simulation training. There are VR tools being used to enhance the way medicine is actually delivered, even in surgical procedures. And there are other areas that we haven’t really tapped into that have been mentioned on this call, AI, machine learning and how those can be used to enhance the patient safety efforts that are going on today by taking all the information that we already have in health care that’s been collected over these 25 plus years and start to apply it to patient safety problems with technology of today. Because as has been mentioned, for example, by Hardeep, you know, we’re relying on people to see the problems in person in the flesh and then report them. And there are a lot of other things at play.

There’s the hierarchy of health care. There’s the human desire to call out a mistake that happened on their own team. Computers don’t really have that problem. And if we could start to pick the brains of the brightest minds out there working in technology to use all this data that’s collected about what can go wrong and what does go wrong so that a computer can identify it before the human does and stop the team or the clinician in their track to say, Hey, wait, we’re going down a track that could lead to harm for this patient. Either you need to double- check the medication you’re trying to prescribe them, or you need to stop and reevaluate the procedure that you’re about to do, that technology exists today. It’s just a matter of finding the people who can turn it into something that a hospital can actually use. And we’ve found that, yeah, when people talk about technology and health care, they talk about ChatGPT, they talk about regulation, they talk about adoption and the doctors and nurses who would have to use it, having to learn it. There’s a lot of doubt and a lot of skepticism about how this is all gonna work.

But I think people say that all the time in industry left and right, and if you really put the effort in, it will work. And so with this documentary, I think we’re finding a lot of people doing the work that we can show and highlight. And going back to my father, one of the things that people always tell me about him is that he was so positive and always finding solutions, and he was not really focused on the blame and shame part of health care that was so pervasive, but really on how do we find the solution to the problems we know exist. That was our mission with To Err Is Human, and that is our mission now with this new film as well. So show, yeah. Look, there’s a problem in healthcare. Preventable harm still exists. We know how to solve some of these problems. And people are working on that. Can we show that work please, instead of just talking about all the problems over and over and over again? Because when you see the work, it just bleeds into other places in health care, they all want to be part of this change. They all wanna be part of the movement towards safer healthcare systems. And I believe that if we can show those projects that are happening today, which we will in this film, will make a difference in people’s motivation to actually start to find new ways to solve old problems.

And then we can start thinking, okay, what’s next? AI, algorithms, computers, taking over the world, all of this crazy talk about the future. It is coming, and I think everybody agrees on that. But if we can find a way to make sure that these new ideas also lead to safer care and not new problems, we’re gonna see all those dreams that my father had for a safe healthcare system come true.

[00:43:27] Karen Feinstein: Thank you, Mike. We’re looking forward to the documentary. As I said at the beginning, revolutions are born of hope and not despair, and the Eisenberg Award gives us that hope. It’s like your dad, very positive, focuses on the leaders of today and tomorrow, and I can’t think of two better awardees than Hardeep and Jason. So thank you from the nation for what you do, what you contribute to patient safety. And it’s just a pleasure for me to have a chance to talk to both of you with Mike here today.

So, to learn more about the effort to establish a National Patient Safety Board and any of the topics we’ve talked about today, please visit npsb.org.

Also, we welcome your comments and suggestions. If you found today’s conversation enlightening or helpful, please share the podcast or any of our podcasts with your friends and colleagues. We can’t improve the effectiveness of our healthcare system without your help. You, our listeners, friends, and supporters are an essential part of the solution.

If you want a transcript or the show notes with references to related articles and resources, that can be found on our website at npsb.org/podcast. Up Next for Patient Safety is a production of the National Patient Safety Board Coalition in partnership with the Pittsburgh Regional Health Initiative and the Jewish Healthcare Foundation.

It’s produced and hosted by me with enormous support from Scotland Huber and Lisa George. This episode was edited and engineered by Jonathan Kersting, and the Pittsburgh Technology Council. Special thanks to Lisa Boyd, Carolyn Byrnes, and Robert Ferguson from our staff. Thank you for listening and please take action, whatever that is, to advance patient safety.